- “This investment is foolproof.”

- “This is a great investment opportunity."

- “You have nothing to worry about."

- “The investment is fully guaranteed.”

- “Your loan will be fully repaid with 16% interest in no longer than a year."

- “I will sell my own property to ensure that you are paid back.”

The potential investor believed he couldn’t have received any more positive assurances that the investment would be successful and so he proceeded with the investment. When the investment tanked, the investor sued for fraudulent misrepresentation.

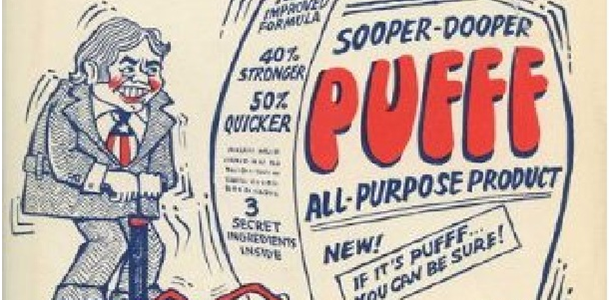

In Scola v. Boivin, a 2016 case decided by New York Supreme Court Justice O. Peter Sherwood on facts similar to those above, the investor lost. None of these statements were deemed to be actionable. The first three statements were deemed to be pure “puffery” or nonactionable expressions of opinion or future value. The next two were deemed to be true statements – the loan was guaranteed and the note did provide that the loan would be fully repaid with 16% interest within one year. The last statement – which was disputed by the defendant - was deemed to be an unenforceable promise and barred by the statute of frauds.

So, what would the investor have had to show to succeed on a claim of fraudulent misrepresentation? As the Scola decision noted the elements of such a claim are “a misrepresentation or a material omission of fact which was false and known to be false by defendant, made for the purpose of inducing the other party to rely upon it, justifiable reliance of the other party on the misrepresentation or material omission, and injury.” Another way of saying this is that to constitute actionable fraud, the false representation relied upon must relate to a past or existing fact or something equivalent thereto, as distinguished from a mere estimate or expression of opinion.

This rule does not completely relieve someone who limits himself to expressions of future fact from liability for fraud. It has been held that an expression or prediction as to some future event, known by the author to be false or made despite the anticipation that the event will not occur, is deemed a statement of a material existing fact, sufficient to support a fraud action. See Green v. Beer, a 2009 Southern District of New York case.

In the same vein, financial projections have been held not to be mere opinions when they were made “knowing that they were false and unreasonable and that they were not based on [the company’s] actual financial condition.” See CPC Int’l Inc. v. McKesson Corp., a 1987 New York Court of Appeals case, which held that projections of expected financial performance constitute “material existing [facts], sufficient to support a fraud action.”

Statements that are recklessly made, i.e., where the maker didn’t know whether the statement was true or false, and was indifferent to whether it was true or false or to the injury which might ensue, may also be the basis for a fraudulent misrepresentation action.

In the Scola case, the investor argued that the statement that the investment was “foolproof” was made recklessly. But, the Court rejected this argument, holding that it was not a representation of fact, but rather puffery. The Court relied, at least in part, on Longo v Butler Equities II, L.P., in which the First Department determined that the “alleged misrepresentations that the target company was seriously Undervalued and could be profitably broken up, and that partnership investors would be 'in and out' in not more than one year, can only be understood as nonactionable expressions of opinion, mere puffing.”

So, what is the rationale behind the rule that statements that are mere “puffing” are not actionable? These statements are deemed to be “nothing more than a recommendation of the [speaker’s] wares. It is common knowledge that dealers are wont to put the best side out, and extol their goods. The public is so familiar with dealer’s ‘talk’ that it is generally regarded as a mere expression of opinion, and, where the parties deal on equal terms, is not relied upon to any great extent.” Koch v Greenberg, affirmed by the Federal Second Circuit, which cited Bareham & McFarland, Inc. v Kane, a 1930 Fourth Department case.